Kansas City Connection Leshnoff’s Symphony No. 3

May 5, 2016

“An Attack: Crossing No Man’s Land” Copyright the Daily Mail

Special Feature by Laura Rollins Hockaday

I was proud and thrilled to hear about Jonathan Leshnoff’s Symphony No. 3 in commemoration of World War I, and that my father, Burnham Hockaday, had a connection to it. Dad would be overwhelmed to think that part of one his letters from WWI would be included in a new symphony. Overwhelmed! He would have been proud and thrilled, too, but he was such a humble man, I am sure he would wonder why his name ever came up.

My father never talked about his WWI experiences. I wish I had asked him about them. I never wanted to bring up harrowing memories. He left Princeton University in his sophomore year, 1917, and enlisted in officer’s training at Camp Funston, Fort Riley, Kan., where he was for about a year, training mostly on horseback. According to my mother, he rode a horse across No Man’s Land [the dangerous land between front-line trenches], gathering information for brigade headquarters, but he never told me this. I had to read excruciating details about trench warfare and No Man’s Land to try to understand what he went through. He was a platoon leader and a 1st Lt. in Company A, 354th Infantry Regiment, 89th Division of the U.S. Army, then called the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). A history of the 89th, which Dad gave me, mentions his bravery and leadership under fire but he never pointed that out – I found it in reading.

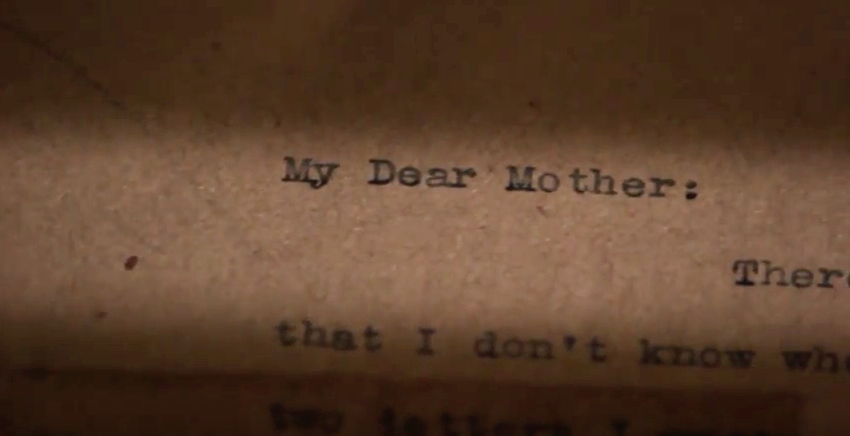

Portion of Letter by Burnie Hockaday

My father lived to be 100; he was born May 4, 1896, and died Dec. 30, 1996. His full name was James Kellogg Burnham Hockaday, but he was known to everyone as Burnie. Long after the war, he had some memorabilia he wanted to give to the museum at the Liberty Memorial, so we went down one day. While there he looked at a display of a trench and its “living” conditions. He remarked briefly that it looked a lot better than what he remembered. He gave the Museum about 25 letters he had written home that his family had saved. I didn’t realize how many he had donated until years later when I wanted to give a talk about my father for my book group and asked the Museum for copies of his letters. What stands out in my mind is that in the letters he never mentions the horror of war or what he had to endure. He never wanted to worry his family back home. He writes to his brother, Irvine O. (Mike) Hockaday about a fight overhead between American and German planes and treats it as a great Fourth of July display.

My father had tremendous respect and admiration for the men in his company. He was devoted to them and they felt the same toward him – I heard this in person from one man’s granddaughter. They were fiercely loyal and were tough, dedicated men. Many of them were hard-working farmers from Missouri and Kansas. Dad kept a roster of them, and as each died, he would write “Taps” beside his name.

Dad spent six months in the trenches of France, fighting in two major battles, the Meuse-Argonne and the St. Mihiel Drive. After the war, he served 18 months in the Army of Occupation in Germany and was responsible for lodging thousands of soldiers. He spoke German before he went overseas and became close friends with a family he billeted with in Trier, on the Mosel River. They owned a vineyard, which was a lovely dividend. Some of the family visited our home in Kansas City years later. Returning home after nearly three years, Dad went back to Princeton and graduated with his brother in 1921. When he died, my father was the oldest survivor of the Class of 1919.

He always attended the concerts of the Kansas City Philharmonic Orchestra and later the Kansas City Symphony with my mother, Clara Hockaday. Next to my dad, music was the love of her life. She was president of the Women’s Division of the Philharmonic for several years and co-founded the Jewel Ball in 1954 with Mrs. R. Crosby (Enid) Kemper, Sr. The Philharmonic desperately needed money to survive and Mother thought a ball at the Nelson-Atkins Museum could raise the needed funds. It did and the Jewel Ball continues to this day.

I adored my father. He will always be a hero to me. He never wanted any glory or recognition. He wanted simply to live a good, honest and decent life and to do right by his fellow man. He would be so amazed and thrilled with the new National World War I Museum and Memorial and this musical commemoration. I wish he had lived to see it.

To hear the Kansas City Symphony, led by Music Director Michael Stern, present the world premiere of Jonathan Leshnoff’s Symphony No. 3, call the Symphony Box Office at (816) 471-0400 or select seats online here. Also on the program in Tchaikovsky’s Third Symphony and Magnard’s Hymne à la justice. Tickets start at $25.

Related Posts

06/18/24

Michael Stern’s Final Concert as Music Director at the Kansas City Symphony to be Streamed Live on medici.tv

03/28/23

Upcoming 2023/24 Season is Michael Stern’s Final Season as Music Director

01/31/23